Co-Folding Models

Building fine-tuning capabilities for co-folding models in pharmaceutical research

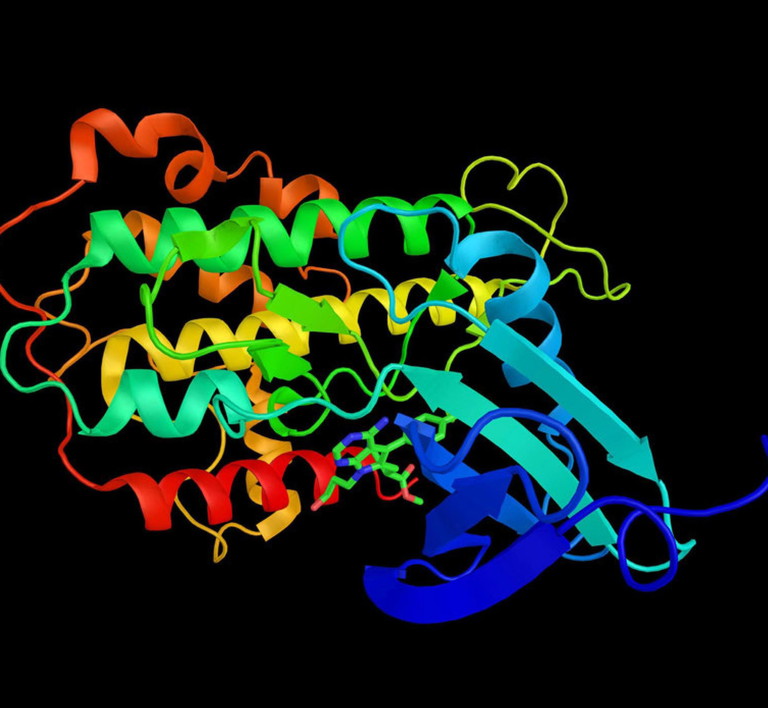

What are co-folding models and how is their use transforming drug development?

Robin Röhm at Apheris

Co-folding models are advancing rapidly but remain uneven; impressive on public benchmarks, less consistent on unseen targets. Models such as OpenFold3, Boltz-2and Pearl improve predictive accuracy and expand the range of systems they can handle, from protein-ligand to antibody-antigen and RNA complexes. Yet, all still struggle with out-of-distribution chemistry and under-represented binding modes. In this environment, progress depends less on the next model release than on how teams use what already exists. The frontrunners will be those who treat co-folding as an iterative, hypothesis-testing process; benchmarking, selecting and fine-tuning models on their own data while participating in secure collaborations that expose models to broader, more diverse chemistry to improve generalisability.

A small but telling observation

Across programmes, the same pattern repeats – a model that looks excellent on public benchmarks underperforms on a new kinase, a challenging antibody epitope or an RNA target. Performance varies with modality and with proximity to the training distribution. The choice of model matters; choosing without in-house validation is guesswork. These discrepancies are not anomalies. Even organisations with advanced artificial intelligence (AI) teams often find that they ‘have the models but not yet the means’ to use them effectively. Building the surrounding benchmarking, validation and data-preparation capability remains the bottleneck – and the opportunity – for extracting real scientific value from co-folding AI. They reflect a broader structural limitation in how today’s co-folding models are trained and evaluated.

Why public benchmarks are necessary but insufficient

The current generation of co-folding models still shows clear boundaries. Most models are trained and evaluated on publicly available protein data bank structures, which limits the diversity of molecular interactions they have encountered. A recent independent benchmark examined precisely this issue.1 The authors compiled a post-cut-off data set of 2,600 complexes and found a nearly linear decline in accuracy as structural similarity to the training set decreased, dropping to about 20% success for the most novel ligand poses.1 The study highlights a key insight: current co-folding models interpolate well within familiar structural space but struggle to extrapolate to new targets and scaffolds. This finding explains why strong leaderboard results often fail to translate into industrial settings, where proprietary chemistries and novel targets dominate. The implication is clear; assessing a model’s applicability domain on internal data is indispensable before use in design cycles. Addressing these limitations requires more than selecting a better model; it requires a system for continuous evaluation, adaptation and governance. In other words, a capability.

What co-folding capability really means

A co-folding capability is not a one-off deployment. It is an internal AI life cycle that treats models as evolving entities whose performance must be continuously validated and adapted to the chemistry they serve. The differentiator is not owning a better model, but operating a coherent workflow where chemists, data scientists and infrastructure teams can test hypotheses on the same models and data sets safely, reproducibly and at scale. A mature capability also extends beyond validation to systematic model comparison and inference optimisation. Different architectures – such as Boltz-2 and OpenFold3 – offer distinct trade-offs in run-time, accuracy and modality coverage. Understanding these differences, and tuning inference performance, is essential for large-scale applications like virtual screening or generative design, where millions of predictions may need to be evaluated efficiently.

As new model versions and architectures now emerge every few months, automation, benchmarking and traceability have become essential controls for credible AI use in regulated R&D. The capability is therefore both technical and organisational: an engineered process that keeps model evaluation, optimisation and governance aligned across teams.

The following workflow is based on industry experience gained from supporting large pharmaceutical organisations in building AI-enabled co-folding capabilities. It enables scientific teams to answer four questions quickly and defensibly, helping them validate different AI models and versions against the tasks that matter most to their research:

Does this model work on my targets and chemotypes?

This question is addressed through systematic in-house benchmarking with clear success criteria, tailored to each modality. For protein-ligand predictions, for example, pose accuracy can be assessed through ligand-pose root-mean-square deviation or local distance difference test for protein-ligand interactions metrics relative to crystallographic structures. Because proprietary targets and ligands cannot be sent to public inference servers, organisations need a locally deployed solution that enables secure model execution, data preparation and benchmarking in one environment.

If it works, how and where can it be used in practice?

Following initial benchmarking, models are compared across versions and successive releases. Automated pipelines for validation and result tracking minimise manual effort and maintain traceability of configurations, parameters and database versions. For large-scale campaigns, such as virtual screening or generative design workflows, the same infrastructure must scale efficiently across graphics processing units and users, supporting high-throughput inference without loss of traceability or compliance. The objective is to maintain an up-to-date view of which model and checkpoint perform best for each programme and task.

If it does not work well enough, can it be improved?

Improvement is achieved through targeted fine-tuning on proprietary structures, sequences and ligand series. Even small, carefully selected data sets can meaningfully shift performance where it matters most. Scalable compute infrastructure and managed resource allocation – such as containerised environments and queued workloads – enable model customisation without sharing sensitive intellectual property (IP) with external providers. Standardised data curation steps, including deduplication, chain parsing and provenance tagging, ensure that inputs are correctly formatted and that the effect of fine-tuning is maximised across programmes.

Can models’ generalisability be broadened?

When a programme explores novel chemistry that internal data cannot represent, federated networks provide a way to extend learning. Partner organisations train models locally and exchange only privacy-preserving model updates, while learning across data sets, expanding chemical diversity and extending the applicability domain of the model. This capability spans people, processes and infrastructure.

It places medicinal chemists and structural biologists in the loop with intuitive review tools, gives computational teams programmatic control for scale and satisfies enterprise security.

From local capability to collaborative generalisation

Even after careful local fine-tuning, model performance remains limited by the diversity of each organisation’s proprietary data. In pharmaceutical research, no single data set spans the full range of chemical scaffolds, binding modes and modalities required for robust generalisation. Federated learning offers a way to extend local co-folding capabilities by enabling multiple partners to jointly train or benchmark models without sharing raw data. Each participant trains models within its own secure environment, and only privacy-preserving updates – such as gradients or low-rank adapters – are aggregated.

A recent example is the Federated OpenFold3 Initiative of the AI Structural Biology Network, in which five global pharmaceutical companies (AbbVie, Astex, Bristol Myers Squibb, Johnson and Johnson, and Takeda) and an academic partner (Columbia’s AlQuraishi Lab) collaboratively fine-tuned OpenFold3 on their proprietary structural data sets. Each participant contributed experimentally determined protein-ligand complexes while retaining full data confidentiality. The shared training process combined learning signals across distributed environments and improved the model’s ability to predict protein-ligand and antibody-antigen interactions beyond any single contributor’s chemical space.

Such collaborations illustrate how collective learning across data boundaries can improve extrapolation to unseen chemistries, helping to build models that generalise beyond what any single organisation could achieve alone.

Conclusion

The frontier is no longer defined by model architecture, but by the discipline of turning these systems into reproducible scientific instruments. That is where AI becomes a dependable tool rather than an experiment. Teams that quickly validate models on their own targets, fine-tune on relevant data for key programmes and are able to collaborate efficiently, will extract significantly more value faster from co-folding models. The advantage is less about chasing a single ‘best’ model and more about a disciplined workflow that turns models into dependable scientific tools.

Reference:

1. Visit: biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.02.03.636309v1

Robin Röhm is the CEO and co-founder of Apheris, where he focuses on building enterprise AI applications and federated data networks for drug discovery. With a background in Medicine, Philosophy and Mathematics, he brings a multidisciplinary perspective to the scientific and computational challenges of working with distributed, IP-sensitive data. His work centres on enabling pharma companies to run, fine-tune and benchmark drug discovery models securely within their own environments and to collaborate through governed data networks without sharing raw data. Before founding Apheris, Robin built life sciences data start-ups working with sensitive genomic and patient information.