Imaging Flow Cytometry

How imaging flow cytometry is transforming cell and protein therapy

Advancements in imaging flow cytometry have improved the detection of particles in pharmaceutical formulations and helped provide insights into how these protein-based therapeutics work

Brian E Hall at Cytek Biosciences

Imaging flow cytometry (IFC) has long been implemented as a critical research tool to better understand cells and cell interactions. Advancements in photonic sensitivity and image clarity have made IFC an increasingly useful tool for measuring small particles, including protein aggregates, bacteria and silicone oil droplets in pharmaceutical formulations. These systems rapidly capture high quality images of particles in flow. Advanced image analysis software tools are employed to mine the image database to measure particle size, concentration, phenotype and functionality. IFC systems are able to analyse a broad range of particle sizes and are effectively used to measure whole cells aand cell-to-cell interactions, thus making them ideally suited to better understand the mechanism of action of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), protein interactions and chimeric antigen receptors (CAR) T-cell therapies.

Importance, features and uses of imaging flow cytometry for translational research

Protein injectables are some of the most effective and in-demand treatments available. These injectables are formatted to target a diverse range of pathologies, including treatment of cancer with mAbs, to management of diabetes and weight loss with glucagon-like-peptide-1 (GLP-1).1,2 This promising therapeutic modality is subject to forming protein aggregates and agglomerates with silicone oil droplets formed from the lubrication used to coat preloaded syringes; thus, testing is critical to ensure that large particles are not generated during shipment and storage.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the US Pharmacopeia recommend rigorous assessment of protein injectables to ensure they are free of bacterial contamination and large aggregates, which can cause immune reactions and alter the effective dose of the medication.3 There are multiple ways to evaluate protein aggregates, including size-exclusion chromatography, dynamic light scattering and flow imaging microscopy (FIM). The typical small particle limit of FIM is around 2μm in diameter, however, advancements in IFC have made measurements of particles smaller than 1μm and well over 20μm in size possible in a single sample.4 Some IFC systems can generate multiple high-resolution images of particles in flow and capture brightfield, fluorescence and side scatter images at rates of over 5,000 particles per second. Images may be captured at either 20x (1μm per pixel), 40x (0.5μm per pixel) or 60x (0.3μm per pixel) resolution, with up to ten fluorescence markers. Captured images maintain spatial registration so that an automated image compensation tool can be used to remove fluorescence crosstalk into adjacent channels on a pixel-by-pixel basis, ensuring that each image displays light exclusively and accurately from its specific marker. The image data is then processed using image analysis software to quantify not only the total fluorescence intensity in the image, but the spatial distribution and overlap with other markers as well. High-speed imaging provides an unprecedented level of sensitivity to visualise small aggregates, and when combined with fluorescence images, enables the simultaneous detection of silicone oil droplets, bacteria and protein-silicone agglomerates. IFC can also quantify fluorescence morphology in whole cells, measure mAb cell binding, help determine cell-to-cell interactions and elucidate the mechanism of action of many protein-based therapies. When combined with advanced machine learning software tools, IFC systems can be trained to automatically identify unique phenotypes such as immune synapse formation, which can be challenging to classify using standard methods.

IFC for pharma formulations

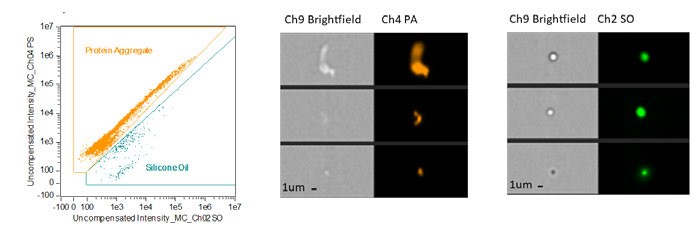

Protein therapeutics provide many advantages for treating a wide array of conditions, including diabetes, autoimmune disease and cancer.5 However, a critical challenge in using protein-based formulations is their tendency to clump, leading to an increase in immunogenicity, lowered effective dose and blood vessel occlusion. Exposure of protein therapeutics to siliconised surfaces found throughout the manufacture and transportation of the formulation can induce aggregate formation and unwanted interactions with silicone oil droplets. The ability of IFC to simultaneously collect brightfield, side scatter and fluorescence imaging means IFC can detect sub-visible and low contrast proteins using a simple fluorescence labelling technique for multiple targets, including proteins, silicone oil and bacteria (Figure 1). This combined approach provides an accurate measurement of protein aggregation and silicone oil concentration as well as protein-silicone oil interactions.6 Each of these particles has the potential to augment immunogenicity against the treatment and induce the formation of serum anti-drug antibodies, leading to an ineffective treatment or worse – inducing a serious health risk. IFC has proven useful in measuring the soluble phase of protein injectables, but the ability to capture high resolution images of cells in flow has become increasingly important to study the cellular mechanism of action of therapeutic outcomes.

Figure 1: Dot plot and images displaying measurements of protein aggregates and silicone oil droplets. Sample fluorescently stained with ProteoStat (orange) to label proteins and PMPBF2 (green) to label silicone oil for identification of sub-micron particles and aggregates over 20μm in a single sample

IFC and mAb therapies

IFC can capture a broad range of particle diameters, ranging from 27nm up to 120μm in diameter, depending on the instrument and magnification being used. At high magnification, systems can collect images at 0.3μm/pixel resolution, which is suitable for measuring colocalisation of mAbs with other proteins in primary blood cells, or observing how bispecific antibodies help immune cells find their targets. The therapeutic anti-CD20 mAb rituximab is used in the treatment of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. This works by binding to B-cells, thus tagging them for destruction by the immune system. Characterising this mechanism of action serves to improve the specificity of mAbs and reduce side effects. IFC was used to measure C3b/iC3b binding and colocalisation with rituximab in Raji cells using an algorithm called Bright Detail Similarity.7 The advantage of this algorithm is that it provides an unbiased measurement of protein colocalisation and helps automate data analysis without the time-consuming step of having to assess each image individually. IFC can simultaneously measure cell health and apoptosis in target cells using morphology-based features, and can be a useful tool for quantifying antibody-dependent, cell-mediated cytotoxicity to ensure the specificity and effectiveness of mAb treatment.8

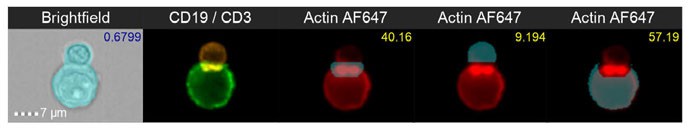

IFC and cell-to-cell interactions

When immune cells recognise and bind to their target, an immunological synapse is formed, comprising a central core of T-cell receptors, surrounded by a series of adhesion molecules. This specialised interface between two cells has a unique morphology that can readily be detected and measured using IFC (Figure 2). Natural killer (NK) cells are members of the innate immune system and function in the normal immunosurveillance of cancers. However, due to the ability of cancer cells to evade immune responses, NK cells often lose their cytotoxic and anti-tumour abilities. To overcome this, a bispecific CD30/CD16 antibody, AFM13, can be used to enhance the potency of cord blood-derived NK cells to target CD30+ lymphomas.9 This enhanced targeting ability also translates to NK cells with genetically modified CAR that are stably expressed on transformed CAR NK cells, enabling them to maintain their anti-tumour effects.10 IFC can accurately measure the binding of NK cells to target cancer cells using a series of immunophenotyping markers to identify each cell type, and a custom morphology-based feature that automatically identifies immune synapse formation. This approach provides robust statistics for each population and the ability to visually verify images in each population to ensure accuracy.

Figure 2: Brightfield and fluorescent images of cell-to-cell interaction between a B-cell and a T-cell forming an immune synapse. CD19 (B-cell) is represented in green, CD3 (T-cell) in orange and Actin (adhesion molecule) in red fluorescence, highlighting the side view of the immune synapse

“ Features such as small particle detection of antibody aggregates and the generation of high quality images of thousands of objects enable accurate enumeration of cells actively engaged in immune synapse formation to determine therapeutic mechanisms ”

Conclusion

Cell and protein therapies hold tremendous potential for treating a broad range of pathologies and enhancing the body’s own tumour-fighting capabilities. These therapies are often more effective with fewer side effects and have better long-term outcomes than traditional treatments. IFC is an invaluable tool to help researchers achieve a deeper understanding of protein therapies. Features such as small particle detection of antibody aggregates and the generation of high quality images of thousands of objects enable accurate enumeration of cells actively engaged in immune synapse formation to determine therapeutic mechanisms. IFC is transforming not only how protein pharmaceuticals are being evaluated and manufactured, but also provides unique insights into how they function.

References:

- Leader B et al (2008), ‘Protein therapeutics: a summary and pharmacological classification’, Nat Rev Drug Discov, 7(1), 21-39

- Vilsbøll T et al (2012), ‘Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1receptor agonists on weight loss: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials’, BMJ, 10(344), d7771

- Wang W et al (2012), ‘Immunogenicity of protein aggregates--concerns and realities’, Int J Pharm, 431(1-2), 1-11

- Probst C et al (2017), ‘Characterization of protein particles in therapeutic formulations using imaging flow cytometry’, J Pharm Sci, 106(8), 1952-1960

- Usmani S S et al (2017), ‘THPdb: Database of FDA-approved peptide and protein therapeutics’, PLoS One, 12(7), e0181748

- Probst C (2020), ‘Characterization of protein aggregates, silicone oil droplets, and protein-silicone interactions using imaging flow cytometry’, J Pharm Sci, 109(1), 364-374

- Beum P V et al (2006), ‘Quantitative analysis of protein co-localization on B cells opsonized with rituximab and complement using the ImageStream multispectral imaging flow cytometer’, J Immunol Methods, 317(1-2), 90-9

- Helguera G et al (2011), ‘Visualization and quantification of cytotoxicity mediated by antibodies using imaging flow cytometry’, J Immunol Methods, 368(1-2), 54-63

- Kerbauy L N et al (2021), ‘Combining AFM13, a bispecific CD30/CD16 antibody, with cytokine-activated blood and cord blood-derived NK cells facilitates CAR-like responses against CD30+ malignancies’, Clin Cancer Res, 27(13), 3744-3756

- Melo Garcia L et al (2025), ‘Overcoming CD226-related immune evasion in acute myeloid leukemia with CD38 CAR-engineered NK cells’, Cell Rep, 44(1), 115122

Brian E Hall is an imaging applications scientist at Cytek Biosciences with over 20 years of experience developing imaging flow cytometry systems and applications. With a background in oncology research using both flow cytometry and confocal microscopy, Brian has been intimately involved in the development and optimisation of imaging flow cytometers and the data analysis software used in these information-rich experiments. With over 25 publications and six patents in the field of IFC, Brian has become an expert in this novel approach to cell analysis.