Peptides

Sustainable and scalable approaches to peptide manufacturing

Process innovations provide opportunities to reduce environmental impact while improving efficiency and product quality

Sharadsrikar Venkatesan Kotturi at Neuland Labs

Peptide-based treatments – including the increasingly popular glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) drugs used to treat diabetes, obesity and other indications – are growing in use for a range of health issues. Although many current peptide therapeutics are delivered parenterally (eg, via injectable or subcutaneous routes), some peptide-based drugs are delivered orally, with additional oral GLP-1s in the pipeline.1 Oral dosage forms require a higher concentration of drug substance than parenteral forms, creating the potential for even greater volume demand for peptide drug substances. This growing demand has intensified the need for sustainable, scalable manufacturing strategies.

Manufacturing active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) for peptide therapies at scale is resource-intensive. In particular, synthesis and purification use large amounts of solvents, some of which are toxic and environmentally persistent. In synthesis, coupling reagents and additives are also used at excess and produce large amounts of waste. Researchers are investigating alternative solvents and innovative processing methods to reduce environmental impact. Meanwhile, manufacturers are exploring advances in artificial intelligence (AI), process analytical technology (PAT), and process modelling and control to optimise existing processes for greater efficiency and less waste. Contract development and manufacturing organisations (CDMOs) with experience in peptide scale-up can be valuable partners in navigating the complexity of choosing the best process to produce a peptide API and understanding how to use cutting-edge tools for process optimisation.

Peptide synthesis

Today, there are two common types of sequential chemical peptide synthesis processes: solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) and liquid-phase peptide synthesis (LPPS). Hybrid or convergent approaches that combine SPPS and LPPS are also used. Each approach has strengths and weaknesses in commercial-scale manufacturing.

SPPS

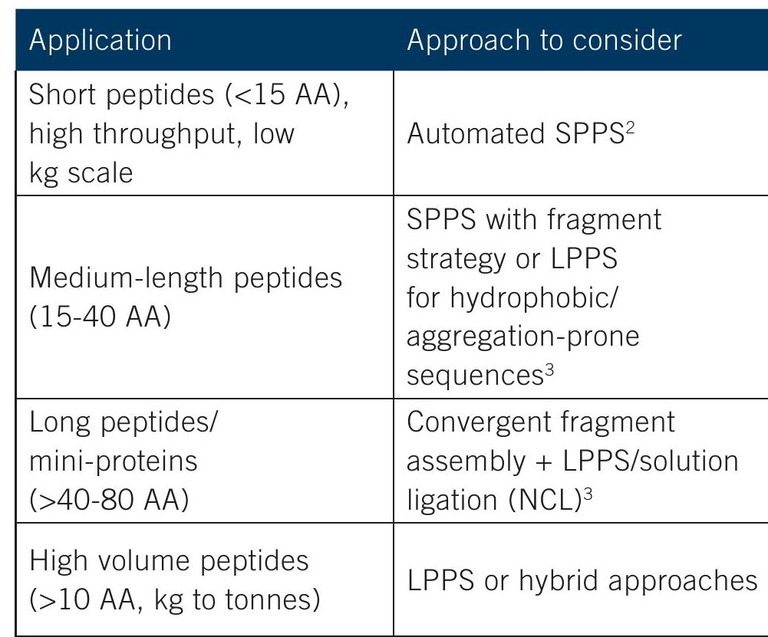

In SPPS, a resin bead acts as a solid support for the peptide while it is built by sequentially adding additional amino acids. For many peptides, the operation is simple, with washing and filtration between each sequential step, compared to the more complex purification required in LPPS. Key benefits of SPPS are that it is fast and easy to automate and control, particularly for short-chain peptides of up to five or six amino acids. As the peptide grows longer, there is a greater possibility of side reactions as well as truncated sequences, when producing at commercial scale. Large volumes of solvents and excess reagents are drawbacks with SPPS. The solid support resin may have limitations associated with resin swelling, porosity, diffusion limits and cost (Table 1).2,3

LPPS

LPPS, or classical solution peptide synthesis, is a more traditional approach for high-yield production of short peptides in solution, with coupling occurring in reactors similar to those used for other pharmaceutical API or fine chemical production. The use of soluble supports or tags (eg, polydisperse polyethylene glycol [PEG], fluorous tags) can simplify LPPS operations and reduce the use of excess reagents and solvents.3 Although LPPS requires purification at each step, it allows fine-tuned control of solvents, reagents and conditions, which is useful for incorporating unusual amino acids, disulphide bonds, or modifications like PEGylation or cyclisation.

Table 1: Various synthesis approaches can be considered depending on peptide lengths (ie, number of amino acids [AA]) and production volumes

When evaluating custom peptide synthesis or planning to scale up a peptide drug candidate, a CDMO partner experienced in all techniques can provide the process expertise needed to handle sensitive sequences. For longer-chain peptides, a hybrid process may be used, in which short-chain peptides are synthesised with SPPS and then combined using fragment condensation in solution to construct a longer peptide. This method can also be used for peptides prone to aggregation.2 Native chemical ligation (NCL) is another alternative that may improve yield and reduce solvent use.4

Other approaches for reducing the environmental footprint in synthesis include using alternative solvents, solvent recycling and continuous flow. A new technology in development is continuous-flow SPPS using micro-reactors that improve heat and mass transfer, and shorten cycle times. Another technology uses continuous percolation washing as an alternative to batch washing to reduce solvent use compared to traditional SPPS.5

A recombinant peptide synthesis approach with enzymatic ligation is an alternative that joins peptides under mild aqueous conditions, which reduces the need for protecting group manipulations as well as reducing organic solvents.

Purification and isolation

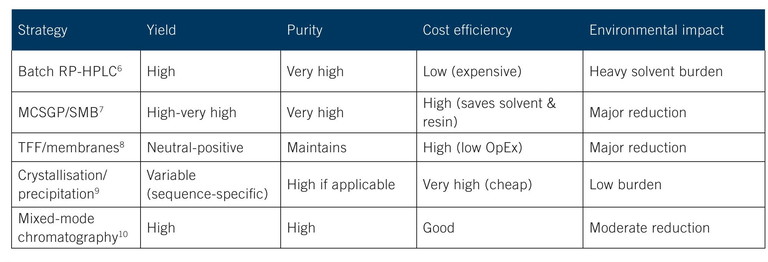

Today, the bottleneck to scaling peptide production is purification. The traditional approach of preparative reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC), also known as dynamic axial compression (DAC) HPLC, is reliable and allows high resolution. However, throughput is low and it uses high levels of solvent – typically acetonitrile (ACN)/water with trifluoroacetic acid – which creates an environmental burden. RP-HPLC purification is typically followed by isolation of the peptide with lyophilisation, which has a high energy demand.

Several technologies are emerging as effective alternatives (Table 2).6-10 Precipitation and crystallisation of intermediates is one way to improve purification. Another is continuous chromatography, which offers cost savings and a lower environmental footprint compared to batch HPLC. Both multicolumn countercurrent solvent gradient purification (MCSGP) for continuous reverse-phase separations or tangential flow filtration (TFF) with a simulated moving bed (SMB) reduce unit operations and solvent loads.

In the longer term, a sustainable purification method to replace HPLC will likely be combinations of membrane operations (eg, TFF) and crystallisation, where peptide solubilities make it possible. Spray-drying or direct crystallisation approaches would minimise lyophilisation and thus reduce energy use.

Solvent recycling

While reducing solvent volume is a key starting point for reducing the impact of process waste, emerging technologies also seek to recycle the solvents that are used. Inline solvent recycling for HPLC seeks to recover ACN from ACN/water mixtures. Manufacturers can also invest in separate distillation and solvent-management systems to recycle solvents and recover energy. For commercial volumes, these tools provide high return on investment.

Effective technologies today

While further innovations are in development, today’s technologies allow improved environmental performance at large manufacturing scales. To effectively reduce process waste, it is important to first measure it in a standardised manner, using calculations such as process mass intensity, E-factor or tools such as the American Chemistry Society’s Green Chemistry Innovation scorecard. A proven strategy for synthesis is to combine SPPS with LPPS in a convergent fragment-based strategy, to reduce the total number of cycles needed, which reduces solvent use. In purification, multicolumn countercurrent chromatography integrated with TFF has been demonstrated at the multi-kilogram scale for therapeutic peptides.11 In these systems, inline solvent recovery loops reduce the need for virgin solvents. These continuous purification methods result in fewer hold steps, lower energy, minimised solvent switches and less material handling. TFF and other membrane-based separations, such as ultrafiltration or nanofiltration, are widely used before or after an HPLC polishing step to remove solvents.

Greener solvents are a current option. In coupling and washing steps, dimethylformamide and N-methylpyrrolidone can be replaced with N-butylpyrrolidone, γ-valerolactone, propylene carbonate or 2-methyltetrahydrofuran. For resin swelling, dichloromethane can be replaced with ethyl acetate or dimethyl carbonate. New types of resins for SPPS (eg, PEG-based ChemMatrix) that are more robust and have better swelling properties in green solvents are also available.

Advanced modelling tools, such as digital twins, can help optimise loading, gradient design and column cycles for maximising productivity. With machine learning tools, conditions can continue to be optimised using ongoing feedback from the process. Today’s automated SPPS peptide synthesisers offer direct communication between lab-scale and commercial-scale equipment, which facilitates rapid scale-up and process optimisation.

Table 2: Purification strategies comparing conventional RP-HPLC to alternatives

Looking to the future

Currently, peptide manufacturing is at an inflection point where the need for more capacity is converging with increased demand for sustainability. Advances in technology, however, offer both more efficient and more sustainable processes. PAT-driven automation and AI, such as digital twins, will allow optimised processes with less waste and tighter process control. Automated SPPS, combined with advanced continuous purification, can support intensified, continuous manufacturing that reduces solvent use and would also support decentralised manufacturing models with smaller, automated peptide plants serving regional demand. As the peptide industry evolves, greener chemistries, such as solvents and reagents with better environmental and safety profiles, can also underpin both scale and environmental impact.

References:

- Shaer DA et al (2024), ‘FDA TIDES Harvest’, Pharmaceuticals, 17(2), 243

- Pennington MW et al (2021), ‘Commercial manufacturing of current good manufacturing practice peptides spanning the gamut from neoantigen to commercial large-scale products’, Medicine in Drug Discovery, 9, 100071

- Sharma A et al (2022), ‘Liquid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (LPPS): A Third Wave for the Preparation of Peptides’, Chem Rev, 122(16), 13516-13546

- Isidro-Llobet A et al (2019), ‘Sustainability Challenges in Peptide Synthesis and Purification: From R&D to Production’, J Org Chem, 84(8), 4615-4628

- Visit: oxfordglobal.com/nextgen-biomed/resources/thefuture-of-peptide-chemistry-and-sustainability

- Andersson L et al (2000), ‘Large-scale synthesis of peptides’, Biopolymers, 55(3), 227-250

- Seidel-Morgenstern A et al (2008), ‘New Developments in Simulated Moving Bed Chromatography’, Chem Eng Technol, 31(6), 826-837

- Zydney AL (2021), ‘New developments in membranes for bioprocessing – A review’, J Membrane Science, 620, 118804

- Wang J et al (2024), ‘Advances in biosynthesis of peptide drugs: Technology and industrialization’, Biotechnology Journal, 19, e2300256

- 1Wan Q-H (2021), ‘Mixed-Mode Chromatography: Principles, Methods, and Applications’, Springer Singapore

- Fioretti I et al (2022), ‘Continuous countercurrent chromatography for the downstream processing of bioproducts: A focus on flow-through technologies’, Adv Chem Eng, 59(1), 27-67

Sharadsrikar Venkatesan Kotturi PhD is chief scientific officer at Neuland Labs, with over two decades of experience in pharmaceutical research and operations. He previously served as senior vice president of Operations at Piramal Pharma, where he led small molecule discovery and the peptides businesses, while driving an ecosystem for innovation. Earlier, he held leadership roles at GVK-Bio and Tata Advinus, following research at RTI International. Dr Kotturi has degrees from University Department of Chemical Technology, Bombay, India, a PhD in Chemistry from Oklahoma State University, Oklahoma, US, and postdoctoral training at Research Triangle Institute. He has authored more than 40 patents and publications in peer-reviewed international journals.